The cooperative way

Recent news

At Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative, many have followed in the bootsteps of their family members. Today, the next generation of lineworkers keeps the lights on, builds new power lines, maintains the electric system and watches out for each other. It’s not just a job — it’s a calling.

Story by Alyssa Meinke

Photos by Sarah Beal

The Lockhart lineage

Four generations in this Central Texas family have carried on a tradition that began in 1917 and continues today at Bluebonnet.

Growing up, Joe M.T. Lockhart briefly dreamed that he might become a second baseman for the Texas Rangers. As they typically do, childhood dreams usually give way to adult realities. “I needed a career that would support a family. It didn’t take long for me to realize that career was line work,” he said.

Line work is what the Lockhart family does. The young man would follow the same path as his father, grandfather and great-great-grandfather.

He is the fourth generation of the Lockhart family to work on electric lines in Texas. The first was Tom Womack, a veteran of the Spanish-American War who got a job in 1917 stringing lines at a Waco military base. Joe M.T.’s grandfather, Joe P. Lockhart, was a lineworker and his father, Joe M. Lockhart, began his career as a lineworker. Now, Joe M.T. Lockhart, 32, is a journeyman lineworker at Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative.

Finding several generations of lineworkers in one family isn’t rare. Bluebonnet employs 118 lineworkers who restore power and help maintain more than 12,800 miles of power lines, and of those, 18 are following in their father’s — or grandfather’s or father-in-law’s — bootsteps.

“It’s an act of service that fosters a sense of pride and connection,” said Joe M.T. Lockhart, who works out of Bluebonnet’s Maxwell service center in Caldwell County.

The work is complicated and dangerous, and, as with police, firefighters and other first responders, line work can become part of who you are. Not many can do it. Communities and rural residents cannot function without the work of people who build, repair and protect the power lines that snake across Bluebonnet’s 3,800-square-mile service area. The lineworkers keep electricity flowing to homes and grocery stores, farms and hospital emergency rooms, small shops and big factories.

Still, the Lockhart family history is remarkable. In a rapidly changing world where fewer and fewer children step into their parents’ professions, four generations in the same challenging career is unusual. The Lockharts also reflect not just one family’s work, but that of the thousands of men and women, companies and politicians who brought electric power to Texas.

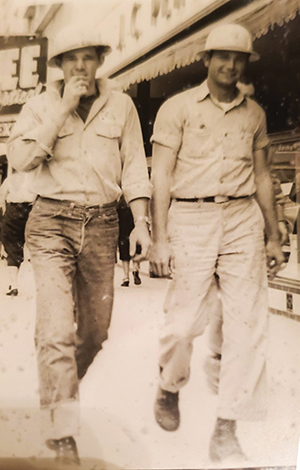

The story has played out for more than a century, beginning during World War I with a man named Foster Boone “Tom” Womack, skipping a generation and continuing through three generations of Lockharts, each named Joe.

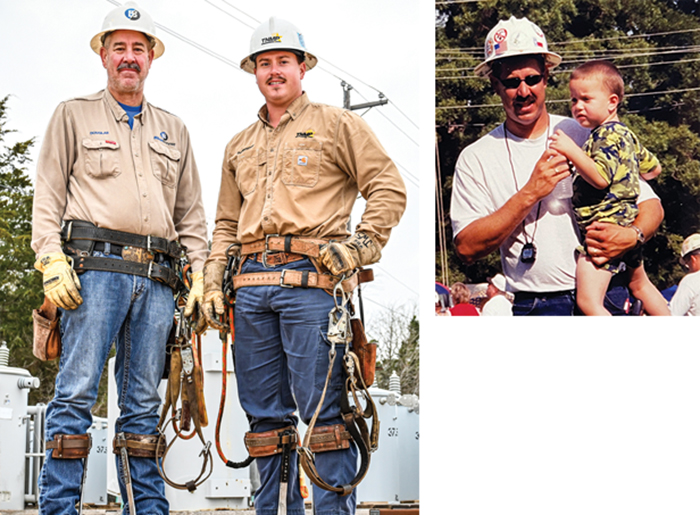

The fourth generation: Joe M.T. Lockhart

As a child, Joe M.T. Lockhart would occasionally go to work with his dad. At age 6, he saw his father on the equipment loading dock as a lineworker. When he was 11, he watched his dad in a control center of Texas Power & Light as power lines were monitored and crews dispatched where needed.

Joe M.T. was 21 and working in the kitchen of the H-E-B Center at Cedar Park, an arena for sports, concerts and shows about 20 miles north of Austin, when he got the call. Heart of Texas Electric Cooperative, based in McGregor, wanted him in for an interview. He immediately told his supervisor, “Man, I’ve got to go. My dream job just called.”

He accepted the job the day after his interview.

Joe M.T. started linework at Heart of Texas in 2013, then spent four years with Nueces Electric Cooperative near the Texas Gulf Coast. After that, he worked for private power-line contracting companies until 2021, when he joined Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative’s apprentice lineworker program.

He completed training and received his journeyman lineworker certification from the Department of Labor in 2022.

On good days, Joe M.T. repairs streetlights and installs new meters and transformers. He connects new service and repairs electric equipment on Bluebonnet’s system. On bad days — when the weather is raging, wind is blowing and outages are occurring — he and other lineworkers brave harsh conditions to inspect lines and equipment, identifying and addressing issues to restore power to the cooperative’s members.

The work is more than just a family legacy. It’s about community, and one story in particular illustrates that.

He was working at Nueces Electric Cooperative, based in Robstown east of Corpus Christi, when Hurricane Harvey hit Texas in August 2017. It is one of many major storms Joe M.T. has worked over the years.

At the end of one 16-hour shift, he and co-worker Robert Vasquez had just finished restoring power to about 100 people on a county road in Orange Grove, 36 miles west of Corpus Christi. “As we were coming down this county road, all the cars had stopped and there were about 40 people on the road, blocking our way out,” Joe M.T. recalled.

The two men were worried that they were about to confront a mob of people angry because they had been without electricity for four days. “We slowly get out of the truck, thinking, ‘What’s about to happen to us?’ ” But to Lockhart’s and Vasquez’s surprise, they were met with water, brisket sandwiches, chips and smiles.

“They gave us their last food and water because we had just gotten their lights back on, and they didn’t let us leave until we finished,” Joe M.T. said. “It made me feel very special. These people just wanted to thank us. That was a big deal.”

Joe M.T. carried that connection to community with him when he joined Bluebonnet. He lives in San Marcos with his 10-year-old daughter, Faith. His parents, Cissy and Joe M. Lockhart, stay with Faith when her father is at work. Joe M.T. Lockhart’s parents understand the demands of the job, because his father worked at electric utilities for 39 years.

The third generation: Joe M. Lockhart

Cissy Lockhart, 64, remembers meeting Joe M. Lockhart in Bedford, 24 miles west of Dallas, in 1985. Joe M. was working for an electrical contractor. “He fell madly in love with me,” she said. Joe M. wanted to marry Cissy right away, but she told him he was crazy and needed to give it a year. So he did.

The couple married in 1986.

At the time, Joe M. was early in his lineworker training, and “line work was all he talked about,” even talking about it in his sleep, she said.

“His father talked about it when they got together,” she said. “It’s just part of their DNA.”

Joe M. became a lineworker in 1985 at Texas Power & Light — now a part of Oncor, an investor-owned electric provider based in Irving. Over time he became a dispatcher, then supervisor of the West Distribution Operations Center. Eventually, he became a district manager for Johnson City-based Pedernales Electric Cooperative, the largest electric cooperative in the United States. He retired in 2022, at 58 years old. He and Cissy now live in Spring Branch, west of San Marcos.

In his time, Joe M. saw advancements in personal protective equipment, fire-retardant clothing, and the shift away from manual and corded tools. But it remained — and remains — tough work.

“You could just about bet by the time a lineman hit his mid-to-late 40s, his shoulders were going to be gone, his elbows were going to be gone and his knees were going to be gone,” he said.

Some aspects of linework remain timeless: stringing power lines, positioning poles and restoring power in the wake of outages. “You still have to plan,” Joe M. emphasized, stressing the unchanged importance of preparation and foresight in the trade.

He learned it from his dad, Joe P. Lockhart, the second generation to carry on the family legacy.

The second generation: Joe P. Lockhart

Joe P. Lockhart started as a lineworker in 1957 at Texas Power & Light and spent 35 years with the company. He was an assistant superintendent in Tyler from 1969 to 1971, superintendent in Hillsboro from 1971 to 1976, and then held jobs in Waxahachie and Euless from 1976 to 1985.

Before he retired in 1992, he was the fleet manager for Texas Power & Light’s eastern region in Tyler. He passed away in 1999, at 59, in Tyler.

Service came naturally to his household. While Joe P. did linework and volunteered in the community, his wife, Kathryn, was an occupational therapist helping mentally disabled adults.

The couple had three children, all of whom would find jobs centered on helping people.

At home, father and son liked to duck hunt together, but Joe M. also got to go to work with his dad.

At that time, lineworkers still mostly scaled poles the hard way, digging spurs into the wood and climbing.

Joe M. recalls the moment, sometime around 1971, when his father, who by then was overseeing all lineworkers at Texas Power & Light in Hillsboro, brought home a new piece of equipment — one of the company’s first bucket trucks.

“They set it up in the middle of the street. We got in the bucket, and I figured out real quick that that was pretty fun,” Joe M. said, likening it to a carnival ride.

Bucket trucks marked a turning point in linework, heralding a new era of efficiency and safety. And the one parked on Joe P. Lockhart’s street more than 50 years ago helped give rise to his son’s career, continuing the legacy started by his grandfather-in-law Foster Boone “Tom” Womack.

The first generation: Foster Boone ‘Tom’ Womack

In 1917, electric lines were just creeping into major Texas cities, often constructed by the military to power streetlights.

After serving in the Army during the Spanish-American War, Foster Boone “Tom” Womack got a job building power lines at Camp MacArthur in Waco, a military training facility created for World War I. The sprawling camp closed down after the war in March 1919, but the power lines Womack built laid the groundwork for Waco’s electric system.

Womack’s daughter, Mary Billon Womack White, told later generations some details of her father’s work. Tom Womack went on to become an engineer, helping design a power plant in Robstown, according to family records.

In the mid-1930s, the Rural Electrification Act unleashed millions of dollars in federal loan guarantees, and power lines began stretching into the rural reaches of Texas. Within a decade, cooperatives, including Bluebonnet, were formed to get power to communities where private utilities saw little chance for profits.

Back then, a house was typically wired for a few appliances, and one overhead light and outlet per room.

Womack passed away in 1938 in Waco. At some point in his career, he started electrical contracting work, wiring Waco homes for electricity for the first time. “My grandmother said these people used to think the house was on fire because of all the light,” Joe M. said. “They weren’t used to that.”

Mary also remembered some unique memorabilia, including the metal hooks her father attached to his shoes to climb poles. Little did she know that the next iteration of these tools would resurface in the hands of her son-in-law, Joe P. Lockhart, bridging the gap between past and present as key to the family tradition of line work.

The evolution and allure of line work

Work on power lines demands a unique blend of physical prowess and technical expertise, and constant attention to life-threatening hazards. Over the years that the Lockharts have been tending the lines, some traditional tools, like Klein Tools’ lineman’s pliers and Super 33+ electrical tape are still in use.

Lineworkers have come to rely on specialized equipment to ensure their safety. This includes fire-retardant clothing, fiberglass tools designed for electric work and battery-powered drills that replaced manual and corded drills.

Hydraulic machines have replaced spears for drilling holes for power poles, further enhancing efficiency while keeping workers safe.

Training and equipment have improved, but lineworkers still must prioritize safety and focus on details to keep them and their coworkers safe.

“It’s a dangerous job and it’s not for everyone,” said Joe M. Lockhart, whose father always told him to “be careful.” That simple, gentle reminder of the challenges of line work is one that has been repeated hundreds – perhaps thousands – of times in the Lockhart family, from generation to generation.

***

Johnnie and Trevor Eckert

Father: Johnnie Eckert, 64

Lives in: Brenham

Years at Bluebonnet: 2000-2020

Previously: Journeyman lineworker

“I had been wanting to start working at the cooperative for a while, but I didn’t want to leave my work with my dad. So when he sold the business, I knew it was time to go to Bluebonnet. I enjoyed being a lineman and learning all I could in my time there.”

Son: Trevor Eckert, 35

Lives in: Brenham

Years at Bluebonnet: 2020-present

Currently: Journeyman lineworker

Previously: Seven years as lineworker for the city of Brenham

“I knew that it was in my blood. I knew what the reward was, as well as the sacrifices.”

Bubba and Trey Townsend

Father: Bubba Townsend, 52

Lives in: Bastrop

Previously: General electrician helper in high school, worked two years at Bluebonnet; lineworker crew supervisor for Austin Energy; lineworker crew supervisor for city of Bastrop

Years at Bluebonnet: 2022-present

Currently: Lineworker crew supervisor

Son: Trey Townsend, 23

Lives in: Rockne

Years at Bluebonnet: 2019-present

Currently: Apprentice lineworker

Previously: Worked on a ranch in Bastrop

“I would tell (would-be lineworkers) what my dad told me when I said I wanted to do this work: You have to be willing to work hard, but it is a very rewarding career. It is great to be able to see a problem through until the lights are back on for members.”

Monroe Bittner, Larry Bittner

and Kyle Kasper

Father: Monroe Bittner, died at 80 in 2013

Worked in: Giddings

Years at Bluebonnet: 1957-1993

Worked as: Journeyman lineworker

Previously: Built telephone lines for U.S. Army

Son: Larry Bittner, 63

Lives in: Giddings

Years at Bluebonnet: 1978-2022

Previously: Journeyman lineworker

“My dad taught me the most out of anyone at Bluebonnet. I worked with him as a helper from a young age. He taught me how to climb on a pole outside of our house.”

Son-in-law: Kyle Kasper, 40

Lives in: Giddings

Years at Bluebonnet: 2005-present

Currently: Lineworker crew supervisor

Previously: Member of Bluebonnet’s first class of apprentice lineworkers

“Larry has taught me how to manage the time away from family, the sacrifices your family has to make because of your job, and how to be there for them. I got pretty lucky with a wife who understands the nature of the job.”

Ernest and Izaac Estrada

Father: Ernest Estrada, 45

Lives in: Gonzales

Years at Bluebonnet: 2010-present

Currently: Contractor inspector

Previously: Lineworker crew supervisor, electrician

“When I joined Bluebonnet, I knew I would be home almost every night. My boys could count on that.”

Son: Izaac Estrada, 24

Lives in: Gonzales

Years at Bluebonnet: 2023-present

Currently: Apprentice lineworker

Previously: Army Reserves

“You have to sacrifice being comfortable. When it is hot, cold, raining, snowing, or any other kind of bad weather, the linemen are out in it.”

Walter, Vernon and Garett Urban

Great-grandfather: Walter Urban, died at 62 in 1965

Lived in: Giddings

Years at Lower Colorado River Electric Cooperative (the co-op's name before it was Bluebonnet): 1939-early ’50s

Worked as: Lineworker

Grandfather: Vernon Urban, died at 42 in 1966

Years at LCREC (Bluebonnet): Mid-1940s-early 1950s

Lived in: Giddings

Worked as: Lineworker

Lineage: His son, Gene Urban, 66, has worked at Bluebonnet for 33 years, and today is the cooperative’s manager of facilities

Great-grandson: Garett Urban, 36

Lineage: Gene’s son, Vernon's grandson and Walter’s great-grandson

Lives in: Giddings

Years at Bluebonnet: 2020-present

Currently: Journeyman lineworker

“It is a great trade to learn, and the field is ever-growing. It’s rewarding when you can get members’ power restored during a storm, but it is also a challenge. You have to be willing to work hard in bad weather.”

David, Douglas and Tyler Grimm

Father/grandfather: David Grimm, died at 67 in 2020

Lived in: Lincoln

Years at Bluebonnet: 1973-2020

Worked as: Lineworker crew supervisor, right-of-way superintendent

Son: Douglas Grimm, 42

Lives in: Lexington

Years at Bluebonnet: 2001-present

Currently: Contractor inspector

Previously: Lineworker crew supervisor

Grandson/nephew: Tyler Grimm, 25 (Douglas’ nephew and David’s grandson)

Lives in: Giddings

Years at Bluebonnet: 2022-present

Currently: Apprentice lineworker

“My grandfather taught me a lot about taking my time with a job. He showed a lot of patience and persistence when teaching me stuff when I was younger. That showed me how I needed to approach line work and the other linemen I work with. My uncle has taught me that you will learn something new every day, and to never stop learning.”

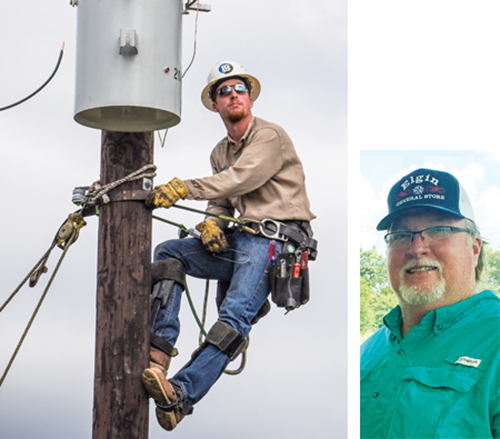

Kenneth and Tucker Saegert

Father: Kenneth Saegert, 52

Lives in: Elgin

Previously: Lineworker at Bluebonnet for two years in the early 1990s; worked at Austin Energy for 29 years, retired

Currently: Returned to work at Austin Energy in 2021, inspecting poles

Son: Tucker Saegert, 19

Lives in: Elgin

Previously: Manager of a Bastrop barbecue restaurant

Years at Bluebonnet: 2022-present

Currently: Apprentice lineworker

“I worried about my dad when he was gone when I was younger, but knowing the guys around him were going to make sure he got home safely made those worries go away as I got older.”

Lloyd Catchings and Joseph Carrillo

Grandfather: Lloyd Catchings, 73

Lives in: Bastrop County

Previously: Began working at electric utilities in 1968; lineworker at LCRA; lineworker and lineworker crew supervisor at Austin Energy; retired in 2023

Grandson: Joseph Carrillo, 31

Lives in: Cedar Creek

Years at Bluebonnet: 2022-present

Currently: Journeyman lineworker

Previously: In the electric utility business since 2011; power-line contract companies

“Being a lineman will teach you a lot about yourself and the things you can accomplish, both mentally and physically. My grandfather taught me to approach a job by breaking it down into steps, and to look for the safest way possible to complete a job.”

Dean and Colton Meinke

Father: Dean Meinke, 61

Lives in: Ledbetter

Years at Bluebonnet: 1983-2020 (full-time, started as lineworker), 2021-present (part-time)

Worked as: Lineworker crew supervisor, maintenance supervisor, other positions

Currently: Part-time maintenance specialist

Son: Colton Meinke, 31

Lives in: Ledbetter

Years at Bluebonnet: 2016-present

Currently: Substation technician; assists lineworkers with power restoration

Previously: Control center operator

“I’ve learned a lot from my dad, from names of parts to field lingo, how things work and their purpose. I call him a lot of times to get his reassurance that I’m doing things right.”

Jim, David, Joey, James, Dalton and Austin Tobola, Phillip Ellis

Father: Jim Tobola, died at 74 in 2022

Lived in: Giddings

Experience: 55 years at power-line construction contractors; majority on Bluebonnet's electric system

Previously: Built communications lines for the U.S. Army

Son: David Tobola, 48

Lives in: Giddings

Years at Bluebonnet: 2002-present

Worked as: Journeyman lineworker, lineworker crew supervisor, field operations superintendent

Currently: Manager of field operations

“The best part about this job is the bonds we have with everyone. They aren’t just co-workers, they are family.”

Son: Joey Tobola, 45

Lives in: Bastrop

Years at Bluebonnet: 2002-2014, 2019-present

Worked as: Journeyman lineworker, field operations superintendent

Currently: Manager of contractor operations

Previously: Lineworker and supervisor at power-line construction contractors

“My favorite part of line work is making something out of nothing and caring for power lines, equipment and people.”

Son: James Tobola, 51

Lives in: Bastrop

Currently: Lineworker crew supervisor at power-line construction contractors

Son-in-law: Phillip Ellis, 48

Lives in: Giddings

Years at Bluebonnet: 2005-present

Worked as: Journeyman lineworker, substation and transmission supervisor

Currently: Manager of technical services

Grandson: Dalton Tobola, 24, James Tobola’s son

Lives in: Bastrop

Years at Bluebonnet: 2024-present

Currently: Journeyman lineworker

Previously: Five years at power-line construction contractors

“Being able to help a team of people working toward the goal of getting the power back on is the best part of line work.”

Grandson: Austin Tobola, 19, David Tobola’s son

Lives in: Giddings

Currently: Lineworker at power-line construction contractors since 2023 high school graduation

Alton and Eric Sommerfield

Father: Alton Sommerfield, 63

Lives in: Brenham

Currently: City of Brenham’s deputy general manager of utilities since 2020

Previously: Lineworker for the city of Brenham since 1979

Son: Eric Sommerfield, 35

Lives in: Brenham

Years at Bluebonnet: 2018-present

Currently: Lineworker crew supervisor in Brenham

Previously: Six years at power-line construction contractors

“When I started, my dad always reminded me to wear my gloves and other personal protective equipment. Now that I have a family, I see why he was so adamant about that.”

Doug and Jakob Schlemmer

Father: Doug Schlemmer, 57

Lives in: La Grange

Years at Bluebonnet: 1984-2006; 2014-present

Currently: Contractor inspector

Previously: Meter reader, line-design technician, lineworker crew supervisor

“I tried to teach him to be safe. Something I always told him is that he should come home the way he left. And that he should always check these three things: hard hat, gloves and ground chains. I still worry about him every day, though.”

Son: Jakob Schlemmer, 24

Currently: Journeyman lineworker for Texas New Mexico PowerPreviously: Lineworker helper at Bluebonnet

Bill and John Matejcek

Father: Bill Matejcek, 69

Lives in: Giddings

Years at Bluebonnet: 1982-1995

Worked as: Lineworker, manager of safety

After: Ten years at power-line construction contractors

“If you want to become a lineman, make sure you go to a good company that cares about their employees, that is very safety-oriented, like Bluebonnet, and learn from them."

Son: John Matejcek, 45

Lives in: Giddings

Years at Bluebonnet: 2005-present

Works as: Journeyman lineworker

Previously: Eight years at power-line construction contractors

“What made my dad a good lineman was his patience in teaching someone who had no idea about the job. You have to do the job safely. That's the priority. So everybody goes home at night.”

Doug and Stephen Braneff

Father: Doug Braneff, 76

Lives in: Bastrop

Years at Bluebonnet: 1985-2006

Worked as: Lineworker crew supervisor, superintendent of operations

Previously and after: 33 years at power-line construction companies

"Even with all the safety practices, there are still elements out there that can be dangerous. A lot of people say you’re not your brother’s keeper, but whenever you’re on a line crew, you are your brother’s keeper.”

Son: Stephen Braneff, 34

Lives in: Bastrop

Years at Bluebonnet: 2023-present

Works as: Apprentice lineworker

Previously: 14 years as a lineworker at power-line construction contractors

“You sacrifice your time away from your family to ensure everyone has power, and as a lineman, there's no greater feeling than to get somebody's lights on who's been without power.”

***

Bluebonnet’s lineworker internship program

Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative offers lineworker internships to hire and train the next generation of employees to master the difficult job.

The intern program began in 2018 and focuses on hiring local candidates, including recent high school graduates. The program starts with six months of classroom instruction and field observation at Bluebonnet.

There is a strong emphasis on safety, which is of utmost importance at the cooperative. Interns receive technical instruction about line work, earn climbing certifications and obtain commercial driver’s licenses.

After that, they start as apprentices, training in the field alongside journeyman lineworkers. After four years — 672 hours of technical instruction and 8,000 hours of on-the-job learning — interns who successfully complete the program can become U.S. Department of Labor-certified journeyman lineworkers.

The program is part of the cooperative’s investment in the communities it serves. It also allows Bluebonnet to continue providing safe, reliable electricity to its members, now and in the future.

Watch bluebonnet.coop and the cooperative’s social media for information about applications and when they will be accepted. For more information about the cooperative’s lineworker training program, go to bluebonnet.coop/careers.

Thank a lineworker

National Lineworker Appreciation Day is April 8. It is a chance to thank the men and women who work day and night, 365 days a year, to build, restore and maintain the nation’s — and Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative’s — power supply system.

Electric cooperatives observe the second Monday in April as National Lineworker Appreciation Day, after a 2014 decision by the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association.

Check Bluebonnet’s social media on April 8 for a video tribute to lineworkers, describing the qualities and skills their jobs entail. You can help us thank the cooperative’s lineworkers by leaving a comment on our video or by sending us a private message.

By Denise Gamino

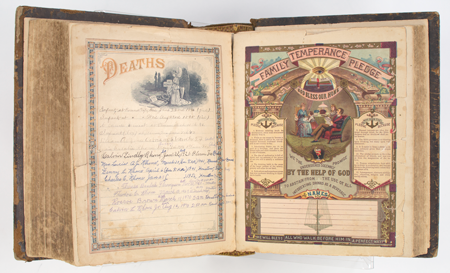

Sometimes, even a chicken coop can be a cradle of history. In 1897, Calvin and Lucia Rhone bought 100 acres in Fayette County. They brought their love letters, financial papers and family photos. They brought their five children and then had four more (another three died at birth). All 12 births were recorded by hand in the big, ornate family Bible.

The Rhones bought 103 more acres in 1917, all within what is now the Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative service area. The family raised turkeys and grew cotton on their 203-acre farm. They also cultivated history.

This respected African-American family, standouts in Round Top as teachers and farmers, preserved scores of personal artifacts that today tell a story of post-Civil War segregation, black perseverance and education, racial integration, family love and the minutiae of everyday life, starting more than a century ago. Treasures include letters from the 1800s, photos of African-Americans and educational records.

The relics were found withering in a chicken coop before being collected by the University of Texas at Austin’s history center, now known as the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History.

The artifacts, called the Rhone family papers, are just the type of household heirlooms that help preserve black history in America. Specifically, they capture some of the character and dynamics of an admired, multigenerational family of middle-class African- Americans in rural Texas.

UT acquired the Rhone family papers in the 1980s, but the surprising story of how they were found and preserved has never been fully chronicled. It involves an airline pilot in Florida who wanted some farmland and his wife, a flight attendant and fifth generation Texan, who wanted to raise their family in the Lone Star State. It involves the Rhone family homestead, found plundered and abandoned outside Round Top. And a dedicated UT archivist who walked into the former Rhone homestead chicken coop, picked up every photo and piece of paper she could find and drove them to her Austin garage in a Volkswagen van.

A UT memo calls the collection “an extraordinarily rich source of information” for studying African-Americans in Texas, “particularly since the collection covers nearly 100 years, with substantial correspondence existing for each decade between 1880 and 1970 (and) numerous excellent photographs.”

“African-American multigenerational collections are not that common,” said Kate Adams, a recently retired UT archivist and curator who retrieved the Rhone collection from Round Top. “There was never any question that we would want this.”

In 1983, Adams was assistant director of UT’s Eugene C. Barker Texas History Center (now part of the Briscoe Center) when she heard about the Rhone keepsakes from a historian at the Texas State Historical Association. A family who bought 50 acres of the deserted Rhone homestead in 1977 wanted to donate the photos and papers.

The donors, Rich and Linda Colby, had found the dilapidated, 800-square-foot Rhone house in disarray when they came from Fort Lauderdale, Florida, to look at real estate in Round Top.

“It looked like somebody had ransacked the whole house looking for valuables and just let it lay,” Linda Colby said. “The furniture was gone, but the papers and things were just there — books, stacks of papers, stacks of magazines like Ebony and things. All kinds of stuff.”

By that time, the last Rhone family member to live in the home had died.

Rich Colby was busy flying for National Airlines out of Miami. Linda Colby, who had been a flight attendant, was a stay-at-home mother and expecting a child. Before the Colbys moved from Florida to the former Rhone farm, Linda Colby’s parents, the late J.F. and Bonnie Knox of Houston, drove on weekends to Round Top to clean the old house.

Bonnie Knox was entranced by the Rhone family’s memorabilia and urged her daughter to save it. “My dad would be cleaning in one room and then he’d go into another room and see my mother reading another letter,” Linda Colby said. “He said, ‘We don’t have all day, Bonnie.’ But thank goodness she had that love of history and preserving things.

“My mother thought there was value to this,” Linda Colby said. “She put it aside. I was not the historian; my mother was.”

Linda Colby’s parents packed the Rhone family papers and photos in boxes and bags. Then, when the Colbys moved in, Rich Colby transferred the collection to the best storage shed on the property: a large, empty, walk-in chicken coop. The collection remained in the coop for several years until the Colbys got to know then-UT professor Jim Ayres, founder of UT Austin’s popular Shakespeare at Winedale program near Round Top. Ayres suggested the Rhone family papers be donated to UT’s history center.

“I just knew it had to do something more than sit in the chicken coop,” Linda Colby said. “I never had the time to go through it.”

The bulk of the Rhone family papers had been collected and preserved by Urissa Rhone Brown, one of Calvin and Lucia Rhone’s daughters who died in 1973. Brown earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Prairie View A&M and spent a long career as a teacher in segregated schools in various Texas towns from the 1930s through the 1960s. She transitioned to the Round Top-Carmine school district when classrooms were integrated in 1966. She served as principal of the elementary, junior high and high schools.

Urissa Rhone Brown and her husband, Roscoe, lived in the Rhone family homestead after her parents died. “She was just such a well-thought-of teacher in this (Round Top) area,” Linda Colby said.

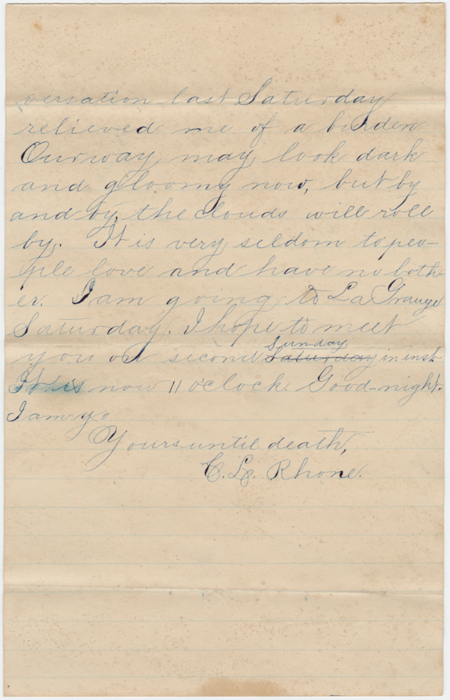

She also was the family historian. Urissa Rhone Brown safeguarded the old family photos and documents as well as thousands of her own school archives and personal papers. And just like her mother had, she saved love letters from her husband.

“She kept everything,” Linda Colby said. “I knew they had to go to be restored and kept for future generations. It was her life’s investment.”

Urissa Rhone Brown’s historical foresight is significant and a model for others, said Michael Hurd, director of the Texas Institute for the Preservation of History and Culture at Prairie View A&M University. It “speaks to the family’s understanding back then of the importance of preservation — telling their story. So many objects of our personal and family histories are summarily tossed, disregarded. However, there’s an increasing awareness about African-American genealogy and the need to tell our stories. And preservation is the linchpin for that.”

That awareness is often heightened during February, which is designated as Black History Month.

Before the Rhone family papers could be processed and archived, UT had to fumigate them twice to protect the collection from mold after being in the chicken coop.

In addition to the papers and photos, the collection includes cotton sacks cut into fabric for dresses, several

colorful church fans with illustrations of Jesus, a calfskin wallet and a powder puff that still contains traces of powder.

The family also kept an 1857 book about the immorality of slavery: “God Against Slavery: And the Freedom and Duty of the Pulpit to Rebuke It, as a Sin Against God,” by abolitionist clergyman George B. Cheever of New York.

Preserved poll tax receipts show that Rhone family members believed their votes were important. The Rhones also were active members of the Concord Missionary Baptist Church in Round Top, founded by African-Americans in Round Top in 1867 and still active today. Calvin and Lucia Rhone also belonged to several African- American chapters of fraternal societies such as the Order of Knights of Pythias, Sisters of the Mysterious Ten and the Grand Court Order of Calanthe, organized in Houston in 1897 to provide burial insurance for blacks.

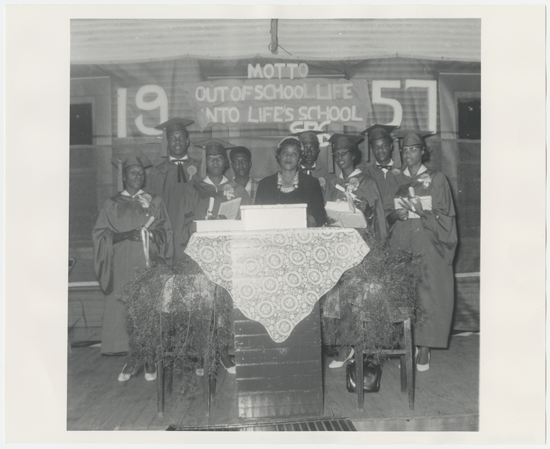

And six of the Rhone children attended Prairie View and became teachers, UT records show.

Urissa Rhone Brown owned a 1924 Model T and paid $11.25 on Jan. 24, 1925, for state license fees, according to the old receipt. She earned a bachelor’s degree in 1947 and a master’s degree in 1955, according to Prairie View A&M University records. Her master’s thesis focused on Round Top High School’s graduation and drop out rates. She concluded that guidance services, classes and student extracurricular activities needed to be improved.

One class paper she wrote as a graduate student in 1950 examined racial inequities: “To my way of thinking, there (are) no essential mental differences in races.” She called racial inferiority a scar “usually caused by shock, disappointment and humiliation.” She argued that a person should be advised that “the color of his skin and/or the texture of his hair does not necessitate his being inferior.”

She wrote those words five years before Rosa Parks refused to give up her bus seat to a white person in Montgomery, Alabama.

“There are still so many stories and aspects of African-American history that need to be revealed, and the Rhone family papers are excellent examples of that,” said Hurd, the Prairie View historian whose institute was created by the Texas Legislature to collect and preserve African-American history and culture in Texas.

“Regardless of where the artifacts were found, so much of them speaks to the family’s understanding back then of the importance of preservation — telling their story.”

THE THINGS THEY SAVED

The Rhone family papers fill 15 archival boxes. Items include:

- Calvin Rhone’s 1903 Fayette County teacher’s certificate for “the colored schools for children.”

- A 1923 receipt for a $1.75 poll tax that Lucia Rhone had to pay for the privilege of voting, just three years after the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution granted American women the right to vote. More annual poll tax receipts are dated through the 1950s before the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that poll taxes were unconstitutional.

- Grocery store receipts showing the family liked vegetables and ham and that someone smoked Camels.

- Motor vehicle fee receipts for their 1924 Ford Model T, license plate 277-525.

- Essays written for classes at what is now Prairie View A&M University, the historically black college 50 miles east of Round Top. One essay about perceived racial superiority states that “there (are) no essential mental differences in races.”

- More than 100 photos, including old tintype studio portraits of unidentified people presumed to be relatives or friends.

THE LOVE STORY OF CALVIN AND LUCIA RHONE

By Denise Gamino

Love can live forever on paper.

“One thought of your sweet smile cheer(s) me in my lonely hours. I get up and imagine you at my side and your bright eyes smiling in mine, and your sweetest voice of all voices ring continually in my ear,” wrote Calvin Rhone to Lucia Knotts in 1887 before their marriage. “I will be true to you until time shall be no more.”

The tenderness and devotion of the young couple began in the 1880s and lasts to this day, because their 130-year-old letters are preserved at the University of Texas at Austin’s Dolph Briscoe Center for American History. Their love story is valued for its details about middle-class African-American life in rural Texas in the decades after the Civil War.

Calvin Rhone and Lucia Knotts married in Round Top in Fayette County on Dec. 27, 1887, and had 12 children (three died at birth). Their 19-month courtship included 37 letters that outlive them. The handwritten letters make little mention of public events, concentrating instead on their relationship. They debated whether Lucia should continue her education at Prairie View State Normal School (today’s Prairie View A&M University) after marriage. She wanted to. He was opposed.

That courtship tension over gender roles was featured in a 1996 scholarly article in Southwestern Historical Quarterly: “The Courtship Letters of an African American Couple: Race, Gender, Class, and the Cult of True Womanhood.”

“By resisting Lucia’s wish to continue her teacher training after marriage, Calvin reflected the values of the dominant white culture,” states the article written by Vicki Howard when she was a graduate student at UT-Austin earning a Ph.D. She now is a visiting fellow at the University of Essex in England.

“At a time when work and marriage were considered incompatible for women, Lucia’s wish to continue her teacher training, and by implication to teach after marriage, was at least contrary to prevailing white middleclass standards,” the article states.

Lucia won out. Both she and Calvin were highly regarded schoolteachers in Round Top, where Calvin was called Professor Rhone.

Six of their children attended Prairie View, including Urissa Rhone Brown, who earned a master’s degree in education there. Urissa’s long teaching career in segregated schools was capped by her role as a much-admired principal in the integrated Round Top-Carmine school district.

Wisdom was her calling. It was she who kept her parent’s love letters for the ages.

This story originally appeared in Bluebonnet's pages of February's 2017 issue of Texas Co-op Power magazine. Download this story