Voices of Veterans

Recent news

This fierce sea creature’s skeleton, spotted a century ago by students, returns to limited public display this year.

By Denise Gamino

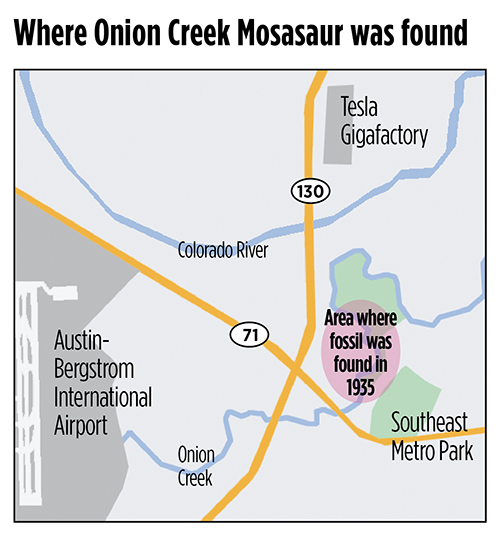

Elon Musk and the Tesla Gigafactory may be the biggest recent sensations in eastern Travis County near the Colorado River, but about 66 million years ago, a truly jaw-dropping phenomenon roamed that area.

SEE THE DINOSAUR PICTURE AND DRAWING SUBMISSIONS

Meet the immense sea creature that got to Texas ages before anyone else.

MORE DINOSAUR SITES IN TEXAS

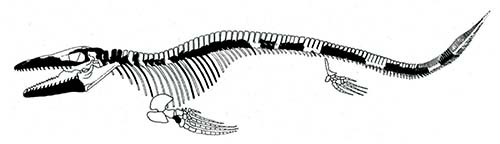

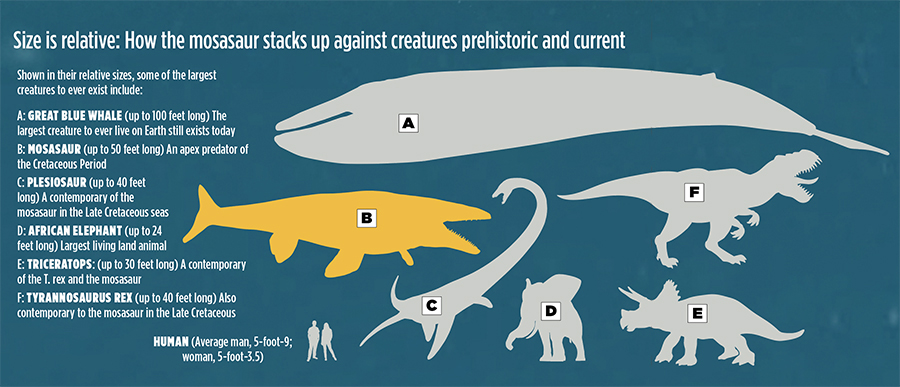

The Onion Creek Mosasaur was a ferociously aggressive 30-foot marine reptile that lived during the dinosaur age. Its 3-foot-wide open mouth and 4-foot-long jaw made it the top predator — and largest animal — in the inland sea that covered much of Texas and 40% of present-day North America millions of years ago. The voracious mosasaurs, swimming in water as deep as 600 feet, “would eat pretty much anything which could fit into their enormous mouths — which, it turns out, was a lot,” according to the National Park Service. Its diet included sharks, fish, birds, ammonites (extinct mollusks) and even other mosasaurs.

The menacing mosasaur (MOSE-uh-sawr) skeleton is the preeminent display at the Texas Memorial Museum on the University of Texas at Austin campus. The museum was closed to the public almost a year ago because of budget cuts, but new funding has allowed behind-the-scenes work to continue. The museum is scheduled to reopen in stages, beginning this fall. The Onion Creek Mosasaur will be seen from afar by visitors at that time, but the public would be allowed a closer inspection of the mosasaur when the second phase of the museum’s reopening occurs in the spring of 2024.

Texas Memorial Museum’s website describes the Onion Creek Mosasaur skeleton as “spectacular.” It’s believed that geologists first saw a part of the giant fossil 100 years ago near present-day Texas 71 and Onion Creek, but the nearly complete skeleton was found there in 1935 by fossil-hunting UT geology students. Those students graduated and went on to have prominent careers in the oil — a fossil fuel — industry.

No one knows whether other petrified mosasaurs may be buried in that area, possibly now covered by roads or buildings. Unlike the federal government, Texas does not require a paleontology review before construction projects begin.

But for at least a century, the area of Onion Creek near today’s Travis County Southeast Metropolitan Park has been known as such a “fossiliferous,” or fossil-rich, spot that it became a favorite specimen-hunting site for UT geology professors and their students. Most finds were oyster shells, clams and other fossilized seashells.

Mosasaurs existed in the Late Cretaceous Period, which geologists believe ended violently about 66 million years ago when an asteroid about 6 miles wide slammed into what is now the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico, causing an enormous inferno and a deadly planetwide dust cloud. The impact is thought to have been as powerful as 10 billion atomic bombs of the type used in World War II. The result was the mass extinction of all dinosaurs (except the forerunners of today’s birds), as well as ocean creatures such as mosasaurs, ammonites and plesiosaurs.

Millennia after that extinction event, on a Saturday afternoon in the fall of 1935, sophomore UT geology students W. Clyde Ikins, from Weatherford west of Fort Worth, and John Peter “Pete” Smith, from Dallas, made the 14-mile trip from the UT campus to the fossil-hunting site on Onion Creek. They were looking for fossilized marine oysters, a common specimen to the area, to fulfill a laboratory assignment.

“We had gone about a quarter of a mile north of the highway bridge on the east bank of the creek when we discovered some bones sticking out of the bank near the water level,” Ikins wrote to UT in the mid-1960s. “We found several vertebrae, rib bones, and a section of the jaw bone about two feet long. The jaw was complete with the large teeth which were used to crush mollusks. The teeth were so well preserved that they had their original polish and luster. At this stage we were very impressed with our find, but had no idea that it would turn out to be probably the most complete mosasaur skeleton that has been found to date.”

Smith was equally proud. “We got a great thrill out of the find as I had been hoping to find one since the day that Dr. (Robert) Cuyler (associate professor of geology) took us on our first Geology 1 field trip,” he wrote in a 1967 letter to UT. “He mentioned that they (mosasaurs) were around, it just took time to find them.”

Ikins and Smith dug out several mosasaur bones that day and brought them back to UT.

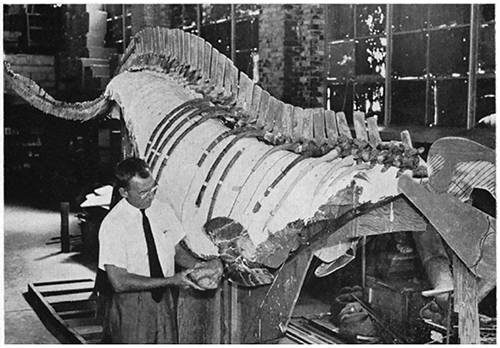

University geology officials were beyond elated by the rare discovery. The prized bones were found just in time to be excavated and showcased in UT’s Gregory Gymnasium as part of a statewide extravaganza to celebrate the 1936 Texas Centennial. They also hoped the mosasaur would bring public and scientific enthusiasm for the Texas Memorial Museum, then in the planning stages. It would open in 1939.

UT’s 1936 Centennial Exposition featured an array of Texas natural science exhibits — such as dinosaur tracks and anthropology dioramas — that drew visitors from all over Texas as well as every other state and 39 countries. The expo ran from June through November 1936, and then cleared out for UT basketball season. It was so popular that visiting hours had to be extended to accommodate the crowds, who could watch the mosasaur bones (except for the skull) being cleaned, preserved and readied for display.

The Onion Creek Mosasaur skeleton “is a particularly lucky find because the specimen is perfect,” noted the late H.B. Stenzel, a geologist who directed the 1936 excavation for UT’s Bureau of Economic Geology, the university’s oldest research unit. His comments were included in a June 7, 1936, UT press release about the Centennial Expo. “With careful supervision, we will have the most perfect specimen of mosasaur yet found in the world.”

Unfortunately, a calamity at the end of the expo delayed the mosasaur’s full public debut at the Texas Memorial Museum for several decades. Workers moving the mosasaur skeleton dropped it, and the bones shattered into many pieces and small fragments. “It remained in this condition for years and years,” Ikins wrote in his mid-1960s letter to the Texas Memorial Museum. “I think the only part of the skeleton that remained in any recognizable form was the head.”

The mosasaur remained asunder until the 1960s, when notable paleontologist Wann Langston, Jr. arrived at UT. He began a two-year process of reassembling the mosasaur skeleton and reconstructing some missing parts so the entire thing could finally be put on public display.

“The paleontologist and preparator reassembled all parts of the skeleton in a natural (swimming) position,” Langston wrote about the mosasaur in a 1966 detailed scholarly study for the Texas Memorial Museum. “As is usual with fossils, some parts of the Onion Creek Mosasaur had been lost before the skeleton was buried and some bones were destroyed by weathering before the discovery was made,” Langston wrote.

“Missing parts were molded in plaster and assembled in their appropriate places among the original bones. These included most of the paddle bones, some vertebrae, ribs, and various parts of the skull and jaws.”

The mosasaur quickly became the museum’s top exhibit when it went on display in the mid-1960s. Ten years later, UT learned that the university’s connection to the mosasaur was older than previously thought.

In 1975, former UT geology student L.T. “Slim” Barrow, the retired board chairman of Humble Oil and Refining Co. (later to become Exxon), sent a letter of congratulations to UT for, among other things, “the perfect job” of reassembling the mosasaur. He said he had been among a group of UT geology students in 1923 or 1924 who had seen some of the mosasaur’s vertebrae at Onion Creek. The students began to dig, Barrow wrote, but “we realized it was too big a job for us and quit before we had done any damage.” Twelve years later, Ikins and Smith found the nearly complete skeleton.

The Onion Creek Mosasaur was far from the only mosasaur that swam the Cretaceous waters that covered much of what is now Texas, while dinosaurs roamed on land. "Fossilized parts of several mosasaur species have been collected from roughly 100 spots in Texas,” said paleontologist and geologist Chris Sagebiel, the current collections manager of UT’s Texas Vertebrate Paleontology Collections. “However, most sites produce only one tooth, or only a bone or two.”

Western Kansas is a hot spot for mosasaur fossils, ranging from single bones to nearly complete skeletons. In Texas, similar “chalk deposits and associated limestone and shale are exposed in a narrow band extending from northeastern Texas (Red River and Bowie counties) southwestward to San Antonio, and westward toward the Big Bend,” Langston wrote in 1966.

“Dallas, Waco, and Austin are all built on these rocks, and mosasaur bones have been found in them, especially in Dallas, McLennan, Williamson, Travis, and Hays counties.”

In 2022, an amateur fossil hunter discovered part of a mosasaur skeleton in the streambed of the North Sulphur River 80 miles northeast of Dallas. Paleontologists from the Perot Museum of Nature and Science in Dallas excavated parts of the fossilized skull, lower jawbone and vertebrae, and plan to continue excavation work.

The exact location of most fossil sites is protected information, and is even exempt from freedom of information laws to preserve them from commercial hunters or vandals, UT’s Sagebiel said. However, the location where the Onion Creek Mosasaur was found is no longer secret because it has been destroyed over the decades by construction on the Texas 71 bridge over Onion Creek. “I believe that the actual (mosasaur fossil) site has since been thoroughly excavated, demolished and concreted over,” he said.

Even with the Onion Creek Mosasaur’s last resting place no longer accessible, Texas still has plenty of ancient creature fossils yet to be found. In fact, the “most fossiliferous site in Texas” is in another part of Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative’s service area, according to the American Federation of Mineralogical Societies. That is a spot along the Brazos River in Burleson County, where a huge deposit of marine fossils includes the remains of snails, oysters, clams and shark teeth.

Collectors have hunted for centuries at that fossil site, under the Texas 21 bridge northeast of Caldwell. Texas A&M University students and science groups still make regular field trips there.

The Brazos Valley Museum of Natural History in Bryan features fossils from the Museum of the A&M College of Texas, which closed in 1965. The Brazos Valley Museum’s collection includes ice age and dinosaur age and casts, including skulls of a mastadon, a triceratops and a Tyrannosaurus rex.

But Texas’ biggest paleontology finds have been made in the Big Bend area of far West Texas. A Texas Pterosaur, with a wingspan of almost 40 feet, was found in that region. You will be able to see its reconstructed skeleton soar in the Great Hall of the Texas Memorial Museum when it reopens in the fall.

***

From fossils to fossil-fuel careers

L. T. ‘SLIM’ BARROW Barrow, who spotted some of the Onion Creek Mosasaur bones in 1923 or 1924, was a native of Manor and played football and basketball for the Longhorns while studying geology. Humble Oil and Refining Company (now Exxon) hired him as a field geologist for surface geologic mapping in Caldwell and Guadalupe counties, where Humble discovered the Salt Flat and Darst Creek oilfields, according to the Texas State Historical Association. He became Humble’s chief geologist in 1929 and rose to chairman of the oil company’s board in 1948. He helped establish a memorial endowment to UT’s Geology Foundation in the late 1950s, in honor of one of his former professors. Barrow died in 1978.

W. CLYDE IKINS One of two UT geology students who found the nearly complete skeleton in 1935, Ikins studied chemistry, botany and geology at UT, earning a doctoral degree in geology. He began his geology career with the Black Mesa Mining Company exploring for brilliant red cinnabar (mercury ore) in Terlingua, near today’s Big Bend National Park. He became chief geologist for Dow Chemical, and later president and CEO of Hondo Petroleum. His botany interests were focused on waterlilies, irises, cacti and succulents. In 1981, he donated his sweeping cacti and succulent collection gathered from around the world to his botanist friend, Dr. Barton Warnock, for a botanical garden in the Big Bend area. Ikins became one of the world’s foremost experts on water lilies and irises. He died in 2005, but today, the peony-like “Nymphaea Clyde Ikins” water lily is still available for sale.

JOHN PETER ‘PETE’ SMITH Smith, along with Ikins, found the nearly complete skeleton in 1935. He went on to become the exploration manager for Esso (Standard) oil’s Libya division and was based in Tripoli. Esso was owned by Standard Oil and became Exxon in 1972. Esso was famous for an ad that encouraged drivers to “put a tiger in your tank” with Esso Extra premium gasoline. Smith retired from Standard Oil in 1967.

History on hold

The Texas Memorial Museum of science and natural history began, appropriately, with a big bang. In June 1936, President Franklin D. Roosevelt set off the dynamite that broke ground for the museum on the University of Texas campus in Austin. Roosevelt, who was on a presidential campaign train trip across Texas, remained on his parked passenger train near present-day East Fourth Street and Interstate 35 while pushing a big red, remote-control button to blast the limestone. The museum temporarily closed to the public in March 2022 because of a staff shortage. However, with university support and fundraising efforts, staff are renovating the museum to open in stages, beginning in September. The Onion Creek Mosasaur will be on display — from a distance — when the museum reopens, but visitors will not be able to get close to it until the second phase of reopening in spring of 2024. The museum is at 2400 Trinity St. in Austin. — Denise Gamino

Meet the Onion Creek Mosasaur!

Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative has received a Platinum Safety Partner award from Texas Mutual Insurance Company. Safety and serving its members with reliable electric service are top priorities for Bluebonnet. Texas Mutual is a workers’ compensation company, and the award recognizes its policyholders that practice top-quality workplace safety. Only 200 of Texas Mutual’s more than 74,000 policyholders are recognized with the distinction annually. The award is given to those that excel at protecting workers and providing safety resources. Pictured in the photo, from left, are Eric Kocian, Bluebonnet’s chief engineer/system operations officer; Heath Siegmund, Bluebonnet’s manager of safety service and compliance; Rachel Ellis, Bluebonnet’s chief administrative officer; and Erika Carral, Texas Mutual’s safety services associate.

Things to do in the Lee County seat

By Alyssa Meinke

The heart of Giddings, home of the high school Buffaloes sports teams, is at the intersection of busy U.S. highways 290 and 77 in Lee County. The town is 55 miles east of Austin and 107 miles west of Houston. It was founded in 1871, after brothers J.D. and DeWitt Giddings financed the Houston & Texas Central Railway, which transported cotton from Houston to Dallas and fueled an economic engine for the region. Giddings was incorporated in 1913, with 2,000 residents, and a 1980s oil boom brought growth. Today Giddings has more than 5,000 residents.

WHAT TO DO

Altman Plants, 1180 Private Road 2906, 3½ miles west of downtown off U.S. 290, is the largest commercial nursery in Texas. You can stop and browse through the assortment of discounted plants for sale to the public from 9 a.m.-2 p.m. Wednesday-Friday, and 8 a.m.-1 p.m. Saturdays. While you’re there, admire its more than 50 acres of massive greenhouses.

Check out one of the state’s largest privately collected arrowhead displays at the Giddings Public Library and Cultural Center, 276 N. Orange St., 10 a.m.-6 p.m. Monday-Thursday, and 10 a.m.-1 p.m. Saturdays.

Also worth a stop is the historic 1879 Schubert-Fletcher Home housing the Lee County Museum, 183 E. Hempstead St., 10 a.m.-5 p.m., Monday-Friday. Although construction partially blocks the view, stop to admire the architecture of the Lee County Courthouse, built in 1899, 200 S. Main St., and the many murals around the city, particularly the historic Depression-era mural inside the post office, called “Cowboys Receiving the Mail,” 279 E. Austin St., which is also U.S. 290. Get more information at co.lee.tx.us and giddingstx.com.

Looking for live music or a screen to watch sports? Check out Giddings Brewhaus, 199 N. Burleson St., from 3-11 p.m. Wednesday-Saturday, and 10 a.m.-3 p.m. Sundays. Home of the “Zoch Bock,” Brewhaus serves craft beers, wines and food, from pizza and hot wings to German specialties like schnitzel.

Before you strike out for home, hit one of the 16 lanes at Leesure Lanes bowling alley, 2249 W. U.S. 290, from 6 p.m.-midnight, Fridays and Saturdays.

GRAB A BITE

Reba’s Pizza & Deli, 208 E. Austin St., 10 a.m.-9 p.m. daily, is a good spot to stop for lunch. It serves homestyle soups, wraps, salads, quiche, specialty pizza and more. Save room for homemade fudge or a scoop of Blue Bell ice cream.

Other dining options ranked in Trip Advisor’s top restaurants in Giddings are:

Los Patrones Mexican Grill, 2880 E. Austin St., 11 a.m.-9 p.m. Monday-Thursday, and 11 a.m.-10 p.m. Friday-Sunday.

Taqueria Chihuahua, 1865 E. Austin St., 5:30 a.m.-2 p.m. Monday-Saturday.

City Meat Market, 101 W. Austin St., 7:30 a.m.-4 p.m. Monday-Friday, and 8 a.m.-2:30 p.m., Saturdays.

STOP AND SHOP

Giddings has several boutiques and gift shops run by local entrepreneurs. Here are three located close together:

Ashley’s Attic, 687 E. Austin St., is a one-stop eclectic shop for gifts, clothes, accessories and Kendra Scott jewelry; 10 a.m.-6 p.m. Monday-Friday, 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Saturdays and noon-5 p.m. Sundays.

Gourmet Divas, at 721 E. Austin St., is a local favorite for cookware, bakeware, spices and kitchen gadgets; 10 a.m.-6 p.m. Monday-Friday, and 10 a.m.-4 p.m. Saturdays. Divas hosts cooking classes periodically; get information at facebook.com/gourmetdivastx.

The Grapevine, 790 E. Austin St., sells gifts, apparel, footwear, home and seasonal decor, plus bags and purses, including those by Consuela; 10 a.m.-6 p.m. Monday-Friday, 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Saturdays and noon-5 p.m. Sundays.

Some other shopping options:

For quilters, All Around the Block Quilt Shop, 979 N. Leon St., 9 a.m.-5 p.m. Monday-Friday, 10 a.m.-3 p.m. Saturdays, is a haven for fabric and sewing supplies.

For antiques, stop by Whistle Stop Antiques, 1122 E. Austin St., 10 a.m.-6 p.m. daily, or Roadhouse Antiques, 791 E. Austin St., 10 a.m.-6 p.m. daily.

Rejuvenation Thrift Store, 179 S. Main St., 9:30 a.m-1 pm. Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays; benefits local residents in need.

TIPS FROM LOCALS

If a train is chugging through town, traffic can back up on either side of the tracks on U.S. 290. If you’re headed west, take a left turn on East Hempstead Street and drive parallel to U.S. 290 to avoid traffic in town.

Take an Instagrammable cruise through town by following the map from the Giddings Chamber of Commerce’s driving tour; get information here.

This is part of a series of guides on spending a day in one of Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative’s service area communities.

All across the Bluebonnet service area are remarkable examples of partnerships with our best friends

Stories by Clayton Stromberger -- Photos by Sarah Beal

Many millennia ago, somewhere in Asia, a gray wolf — hungry, curious, wary — cautiously inched its way toward a human campfire. Eye contact was made, perhaps a scrap of food was tossed over. In an ancient world where survival was elemental, a new partnership was forged.

Ever since that moment, our two species have been intertwined in a complex evolutionary dance, seeking a mutually beneficial relationship. When humans first came to this part of the world, dogs came with them.

We all know the dog’s status today as humankind’s best friend. We have closer connections with canines than any other species on the planet. It only makes sense that they have evolved into work partners. But what kind of co-workers do they make?

FIND PET ADOPTION RESOURCES HERE>>

Pretty great ones, say the owners and handlers of the working dogs of the Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative service area. “These working dogs are amazing,” says Giddings Police Officer Jack Nickell, whose canine partner Bery, can detect drugs. “I learn something new every day.”

All across the Bluebonnet service area are remarkable examples of these unique partnerships. In these pages, we take a look at the many ways amazing canines contribute to the quality of life in our area and share stories from their human partners.

DRUG DETECTION DOG, Bery

Lee County

Bery means business. Like many trained police dogs, the 2½-year-old Belgian Malinois is driven and focused while on the job, to the point of being a bit impatient with his partner.

“When we’re training, if Bery alerts on something and I don’t reward him quickly enough, he’ll look back at me and smack the vehicle with his paw,” says Giddings Police Officer Jack Nickell, the dog’s handler and owner. Bery and Nickell, at right, have been a dynamic duo on the drug-detection beat in Giddings since March 2022. Bery had 160 hours of training, and his nose has led to several arrests.

Nickell bought Bery with his own money while working in 2021 for a different police department that didn’t have funding for a K-9 patrol.

“I like getting narcotics off the street, and I love dogs,” Nickell says, “so K-9 work is something I’ve always wanted to get into.”

CATTLE-HERDING DOGS

Bastrop County

The dogs whirl and wheel around the herd of cattle, barking and closing their circle, working in close tandem with two men on horseback. The object is to move these recalcitrant cattle from the pasture into their pen.

This team of black-mouth curs, most of them siblings, will keep a tight rein on these cattle until the job is done. They belong to one of the riders, Thres Jarosek, 20, who was given the dogs by family friend and Smithville resident Troy Tiner, who helped raise Jarosek after the young man’s father died. Jarosek and Tiner still work cattle together, as they have for most of Jarosek’s life.

“I grew up with these dogs’ grandpas, and great-grandpas,” says Jarosek, who was helping herd on horseback when he was just 4.

Jarosek and his dogs live near Smithville and travel around Bastrop County and outlying areas, herding cattle that decide not to budge.

“It’s pretty cool,” Jarosek says of his day job. “There aren’t many people around that still own cowdogs and have the skills to pen even the wildest of cattle.”

Rugged and resilient, the black-mouth cur (shown herding, above) has long been valued in the southern United States as a tireless herding dog, a courageous hunter of hogs and other wild game, and a loyal and trusty companion back at the homestead.

The title character of “Old Yeller,” the classic 1956 children’s novel by Texan Fred Gipson, is thought by many to have been based on a black-mouth cur — despite any breed confusion caused by the Disney film version, where Old Yeller was played by a Labrador retriever.

Jarosek, who works with these dogs as cattle wranglers, is a fan of the breed. “These dogs,” he says, “are more valuable to us than having 10 cowboys behind the herd trying to control them.”

THERAPY DOG, Griswold

Hays County

It’s finals week at Texas State University in San Marcos, and everyone’s feeling the stress — which makes the appearance of therapy dogs on two floors of the busy Alkek Library especially welcome.

Dog-owner teams from Divine Canines, an Austin-based nonprofit, have been visiting the Texas State campus during finals week since spring 2013. Students line up to take a 15-minute break to chill out and pet dogs such as Griswold, at right.

The Brittany spaniel-border collie mix is hard at work in a characteristically blissful sprawl on the library floor.

“I hear so many students say, ‘Oh, you don’t know how much I needed this today,’ ” says Michele Evans, Griswold’s owner. The pair have been working together for five years.

“Studies show that just having a dog and having that interaction helps lower blood pressure and calm people’s nerves,” Evans says.

Being friendy isn’t enough to get this job: After six weeks of training the dogs must pass the American Kennel Club’s Canine Good Citizen test before helping soothe folks in Hays, Travis and Williamson counties.

ACCELERANT DETECTION DOG, Ember

Travis County

For centuries, the Dalmatian was considered the classic firehouse dog — a tradition that began in New York City in the 1870s, when the gifted runners would trot ahead of the horses pulling the fire carriage and help clear the street of pedestrians.

Today, there’s a new type of job description for four-legged helpers in firehouses: accelerant detection K-9. At Travis County Emergency Services District No. 12 in Manor, Ember — a 1½-year-old Belgian Malinois — rides on every call with Fire Chief Ryan Smith, at left, and is ready to sniff her way through the ashes of a burned-out house or car to determine if an accelerant was used to start the fire.

“She’s an amazing addition to our toolkit,” Smith says. “These dogs can find one-thousandth of a teaspoon of an accelerant in a 100-by-100-foot field in 5 seconds.” Ember’s arrival in fall of 2022 was thanks to a grant from K9s4COPs, a College Station-based nonprofit. She was trained at Pacesetter K9 in Liberty Hill, where she learned to detect traces of 14 different accelerants used to deliberately start fires.

PTSD SERVICE DOG, Patton

Washington County

Life is better for Robert Kilpatrick since General George S. Patton arrived on the scene. Patton, a 5-year-old Great Dane, is Kilpatrick’s post-traumatic stress disorder — or PTSD — service dog. Kilpatrick served his country on nine tours of duty in the U.S. Army, from Operation Desert Storm in Kuwait through missions in Iraq.

The memories of what he saw and experienced are like a “Pandora’s box,” he says, which he attempts to keep shut. But a loud noise, a sudden movement or an overcrowded store can bring back the trauma of combat. That’s when Patton steps in.

“If Robert’s had a bad day,” says his wife, Amy, “Patton will come up and Robert will start rubbing and petting Patton, and you can see everything melt away.”

Patton is trained to serve as a buffer between his owner and crowds and to lead Kilpatrick away from stressful settings.

The dog was trained by a family friend who specializes in training Great Danes to be veterans’ PTSD dogs. Patton has been with the couple for five years. With Patton by his side, Kilpatrick can more easily go shopping and speak to strangers in public.

“He mellows me out,” the Brenham resident says. Patton’s vest is made from one of Kilpatrick’s uniforms.

FIELD CHAMPION SETTER, Melt’n

Lee County

Sometimes a dog just has a gift. Melt’n, at right, a 7-year-old American Kennel Club field champion Irish setter, was sent as a youngster with two siblings to a professional agility-competition trainer in North Dakota, and came out “head of the class,” says his owner, Bill Rhodes of Lee County.

“He completed his training three months early. The trainer sent him back and said, ‘He knows everything I can teach him, so just run him now.’ ” Setters are named for their instinct for finding birds by scent and then “set” in a statue-like position to indicate the bird’s location. “Bird dogs want to please you,” Rhodes says.

In field competitions, the dogs are judged on how well they perform in a simulated bird hunt, guided at key points by their owner. Rhodes is a fan of Irish setters and calls his property “Setter Downs” — part of Melt’n’s official AKC competition name: Field Champion Setter Downs Hot Stuff.

SENIOR LIVING FACILITY THERAPY DOG, Skye

Washington County

When Skye and her owner, Liane Pomfret, walk through the doors of Silversage Assisted Living and Memory Care in Brenham, faces light up and hands reach out.

Skye — a 9-year-old rescued terrier spaniel mix — has a knack for connecting with people. She often reminds Silversage residents of their own beloved pets from long ago. As the years fall away, a conversation begins and happy memories are shared.

“It’s a very strong emotional reaction sometimes,” Pomfret says. “I’ve had Alzheimer’s patients speak when they haven’t talked in weeks.” Pomfret and Skye — who live in Burton in Washington County — are part of Pets With a Mission, a nonprofit based in The Woodlands township north of Houston. The two also visit Brenham Nursing and Rehabilitation Center, as well as area schools and libraries. The duo have worked as a volunteer team for six years.

The key to a great human-canine team starts with the owner, Pomfret says. “If the human is making sure that the dog is happy and comfortable, that’s when things work. That’s when the magic happens.”

CHAMPION SHOW DOG, JLo

Bastrop County

Herr Dobermann, the tax collector for Apolda, Germany, had a problem. When making his rounds back in the 1880s, scofflaws often greeted him not with payment but with a pummeling.

Fortunately, Louis Dobermann also ran the Apolda dog pound. So he decided to breed the perfect personal protection dog. The result was a canine that was alert, smart, fiercely loyal, and both tough and nimble — and eventually the breed came to be named after him. The American version is known as the Doberman pinscher.

Professional dog handler Aslynn Rose of Cedar Creek has long loved Dobermans, and currently owns five of them, including JLo, who is named for the singer. Rose shows her own dogs when she can and JLo — whose registered AKC name is Champion Whiskey Mac’s Lush Life — has appeared at many American Kennel Club show competitions and earned a breed championship.

“They’re unlike any other breed,” Rose says. “In my opinion, they’re the best breed out there — they’re loyal, they’re intuitive, they’re loving and they’re totally committed to you.”

One heads-up: They’re not outside dogs and will always want to be at your side. “You’ll never go to the bathroom alone again,” Rose says.

TREEING HOUNDS, Annie (right) and Slick

Burleson County

When English settlers arrived in Virginia in the Colonial era, they encountered a new animal to hunt for its fur and meat — the raccoon, native only to North America. The settlers imported foxhounds, which excelled at giving chase, but they would lose raccoons once the animals shimmied high up a tree.

Careful breeding eventually led to the treeing Walker hound, first recognized as an official breed by the American Kennel Club in 2012. The hound is known for its ability to “tree” a raccoon and keep it there. Treeing raccoons with dogs has a long history in Burleson County, where Robert Campbell and his dog, Slick (above, left) and fellow Walker hound Annie, can be found keeping the tradition going most weekends on rural family land near Caldwell.

Today, competitive raccoon hunting is for sport, not income or food. The animals are treed and then left alone, or caught and released. The key to a winning Walker? Good bloodlines and practice, Campbell says. “You’ve got to put in time in the woods.”

IRS EXPLOSIVE-DETECTION DOG, Cane

Travis County

Cane, a 7-year-old yellow Labrador, is the first line of defense for Internal Revenue Service employees at the Austin tax-return processing office in south Austin. Under the guidance of handler David Newell, an Air Force veteran, former Taylor police officer and Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative member, Cane gives a good sniffing-over to every package that is mailed, shipped or delivered to the IRS facility.

The Lab is trained to detect the odors of as many as 20 different ingredients used to make explosives — a feat that neither humans nor machines can replicate.

“When you walk into a hamburger place, you smell a burger,” explains Newell. “But a dog can smell the meat, the ketchup, the bread, the yeast, the sugar, the lettuce — they can break it down into every ingredient.”

Cane, at right, and Newell also spend time in Washington, D.C., where they help keep other federal facilities safe from explosives.

HUMAN-REMAINS DETECTION DOG, Dexter

Caldwell County

Texas Game Warden Kryssie Thompson knows the work she does with her partner Dexter — a 7-year-old German shepherd mix — is sensitive and extremely important.

“When I thought about whether to take this job,” Thompson recalls, “I put myself in the position of the family of a missing person. If every asset has been utilized and your loved one is still missing, surely there’s got to be a last line of defense.”

Dexter is one of two human-remains detection dogs brought on by the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department five years ago. They are considered full-time “game warden K-9s.”

Thompson and Dexter were originally based out of Bastrop but recently moved to Huntsville, and they can be called upon for searches across the Bluebonnet service area. At left, they practice a training scenario along the San Marcos River.

When someone goes missing on water or in the woods, and officials suspect that person is deceased, Dexter’s finely calibrated nose can detect odors, sometimes months, or even years, after a death.

He can even indicate the location of victims in water from a boat, often in areas where divers or searchers face limited visibility.

It’s difficult work, but the relief families feel when a lost loved one is finally recovered is often palpable, Thompson says. One family was so touched by their work they sent the duo a thank-you note.

AIRPORT EXPLOSIVE DETECTION DOG, Kan

Travis County

Each workday morning, when Austin police officer Estanislao Rodriguez begins putting on his uniform, his trusty partner, Kan, can’t contain his excitement.

“He goes nuts and starts running circles in the backyard,” Rodriguez says. “He knows we’re going to have fun, because work for him is just play.”

Kan, an 8-year-old Belgian Malinois, was born in Germany, then trained in explosives detection at Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Kan and Rodriguez are one of four K-9 teams used by Austin’s police department to screen luggage and packages at Austin-Bergstrom International Airport.

The presence of the K-9 patrols at the airport, a familiar sight to many travelers from the Bluebonnet area, is a strong deterrent, Rodriguez says. So far, fortunately, Kan, at right, has not detected any explosives while on the job. The dog is retiring this spring at age 9 and will kick back as part of the Rodriguez family.

“You build such a great bond with these dogs,”

Rodriguez says. Kan’s final assignment is an exciting one. He will be one of the dogs helping keep the crowd safe at the 2023 Super Bowl in Arizona on Feb. 12.

LIVESTOCK GUARD DOG, Buddy

Fayette County

Coyotes, be forewarned: Don’t mess with Buddy’s goats. The 4-year-old Great Pyrenees — seen here at his goat-pen home not far from the main square in Round Top — comes from a long line of legendary flock protectors. Great Pyrenees take their name from their ancestral homeland in the rugged Pyrenees Mountains, which form a natural boundary between Spain and France.

There, the breed has long been known for working with shepherds to safeguard herds from predators, even at night. Buddy belongs to Michael and Jackie Sacks, who until recently owned Round Top Mercantile. Buddy guards the family’s eight Spanish Boer goats. He keeps unwelcome visitors at bay and will even take off after turkey vultures if they soar too closely overhead.

“He just kind of goes where the goats go,” says Jackie Sacks. “When they go lay under the trees, he does, too. He probably thinks he’s a goat.”

GAME BIRD POINTER, Sugar

Caldwell County

“The Cadillac of bird dogs” is what a recent American Kennel Club article dubbed the English pointer, lauded for its athleticism and elegant pointing pose. Legend has it this breed originated in 1713, when English soldiers came home from a war in Spain accompanied by Spanish pointers. When a hunting pointer — such as Sugar, at right, in action at Tenney Creek Outfitters in southeast Caldwell County — catches a whiff of a bird’s scent, it freezes with its nose out, one front leg cocked up and its tail in the air. The statue-like stance is an instinctive response refined through breeding and developed with training. Sugar’s job is to help the clients of Tenney Creek owner Jack Chamberlain find quail or pheasant in the underbrush on the company’s property, a private bird hunting area. “Sugar is by far my top dog here,” Chamberlain says. “She can go in and find birds when other dogs can’t.”

Doggone inspired to get a pet? Start with these resources

No matter where you live in the Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative service area, there is a rescue dog waiting for you at a nearby animal shelter. Get more details on these and many other animal shelters in Bluebonnet's region here.